You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

NAMIBIA: Namibia Safari With Kowas Beginning To The End

- Thread starter Toby Bradshaw

- Start date

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

7 July 2014

Every hunter who dreams of Africa wants a trophy kudu. On my 2007 safari to Zimbabwe I had seen quite a few kudu cows and young bulls, but the several mature bulls that we saw melted into the mopane forest before I could get on the sticks.

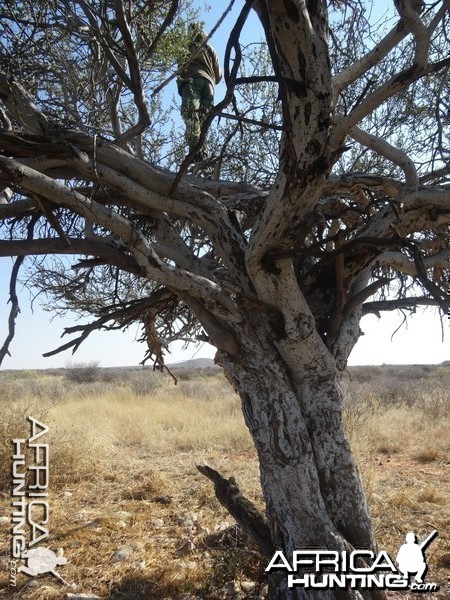

I had some concerns about my prospects for kudu at Kowas, too. Kudu in Namibia have been suffering from a rabies epidemic, apparently spread from animal to animal via their saliva, gaining entry to their bloodstream through the thorn scratches in their mouths. It’s easy enough to imagine that any browser in Namibia would have a sore mouth – virtually every shrub and tree has thorns (see camelthorn photo below).

Matheus told me that 105 kudu skulls, nearly all of them from kudu killed by rabies, were found on the property adjacent to Kowas in the past year.

On the upside, Johnny (JGRaider) and Team Fet had collected some very fine kudu at Kowas recently, and even after just one day of hunting I had a great deal of confidence in Matheus’s ability to find and stalk game.

This morning was a carbon copy of yesterday’s – cold and clear, with the francolin wake-up call coming right on time. I bundled up in all the clothes that I had, wolfed down another rib-sticking breakfast, checked the scope power setting on my rifle, and met Matheus and Michael at the bakkie just before sunrise. Because David and Claude were bowhunting on the Kowas property again today, Matheus had planned our kudu hunt for another neighboring farm, belonging to Harry and Alta Erasmus, part of the 400,000 acre (>600 square miles) Dordabis Conservancy.

Unlike the Seifart farm, which is flat, the Erasmus farm had many rocky hills framing the central valley. Kudu love the acacia-covered hills, and we hoped to catch an old bull warming his bones in the early morning sun after a bitter night on the veld.

The Erasmus farm is only a few minutes away up the main gravel road (C23) from Kowas, but our bakkie was suffering from frost on the inside of the windscreen again. However, this time I was prepared. Matheus had shown me a few tricks in the field, so I returned the favor. I pulled a plastic hotel key card out of my backpack and neatly scraped clean my half of the windscreen and side window, producing a double handful of of ice shavings in a few seconds. Matheus laughed appreciatively, tossed his useless windscreen rag onto the dashboard, and employed the new tool to give himself a panoramic view of the road. That key card/ice scraper is now part of the bakkie’s kit.

Unfortunately, none of this cold-weather technology did Michael any good. He was stuck in the back of bakkie, freezing, again today. Luckily, by the time we got to the Erasmus farm gate the sun was painting the hillsides that gorgeous tangerine color that only seems to happen in Africa. Matheus and I climbed into the back of bakkie, while Michael took over the driving duties.

On the 2-track entering the farm we drove across the valley floor. We surprised a duiker, which panicked when it couldn’t find its usual hole through the cattle fence. After bouncing off the fence a few times, it see-sawed down the road a little farther, in that rocking horse gait peculiar to duikers, and ducked through the next hole.

Matheus pointed out the springbok rams defending their individual territories, creating an evenly spaced pattern of males, with the ewes wandering freely between territories. I didn’t know it at the time, but Matheus was already sizing up those springbok rams for a future hunt, making a mental note of the best trophies.

After crossing the valley, the 2-track climbed partway up the hill and then turned to contour along the hill about a hundred feet above the base. From our elevated vantage point we had a commanding view of the valley floor, and could see across to the hill on the opposite side of the valley. Giraffe browsed in the camelthorn savannah, and black wildebeest were frolicking in the open plain in a mixed herd with some springbok.

The 2-track on the hillside was tough going for the bakkie – very rutted and rocky. A bat-eared fox peered at us from the fenceline along the “road.” Much of the blackhook acacia on the hill appeared to be dead. Matheus confirmed that it had been poisoned by aerial herbicide application, to provide more moisture for the grass that the cattle use as forage. Indeed, the poisoned areas had much more abundant grass cover than the unsprayed patches. However, kudu are not grazers but browsers, and dislike sharing their habitat with cattle. Matheus said, “We must drive along the hill until we come to a place without cattle.”

We rattled along the 2-track for several miles, seeing quite a few kudu cows and calves, but no bulls. We crossed the valley and drove back along the flank of the hill on the other side of the valley.

Suddenly, Matheus tapped the top of the bakkie and whispered to Michael, “Stop behind the tree.” Michael parked the bakkie behind a camelthorn acacia growing right beside the road. Matheus whispered in my ear, “Kudu! A bull watching 2 cows.” He pointed to the crest of the hill 500 yards directly above us, where the two cows were silhouetted, feeding. The bull was 150 yards from the cows, just below the crest, dividing his time between watching them and pulling leaves off the acacias.

Matheus hopped out of the bakkie, using the tree for cover, and I handed him my rifle. As soon I was on the ground, Michael drove the bakkie out of sight. Matheus and I located the kudu bull in our binoculars. I didn’t know what Matheus was thinking, but I had looked at a lot of kudu photos in preparation for my safari, and this bull certainly looked plenty good enough to me!

Unfortunately for us, the kudu was not watching the departing bakkie. He was looking straight at us, or at least straight at the tree under which we were kneeling. As the minutes passed, Matheus never took his binoculars off the bull. When the bull finally turned his head to continue browsing, Matheus crouched down low, motioning for me to do likewise and stay close behind him. We quickly covered the 25 yards to a chest-high blackhook acacia without alarming the kudu bull, which continued to feed slowly towards the cows.

The hillside was covered with canteloupe-sized scree, which made the stalk more difficult. The rocks were unstable, and the ground was so dry that the acacias were mostly short and widely spaced. Every dash to the next bit of cover risked detection by the kudu. Nevertheless, thanks to Matheus, over the next half hour we made good progress, closing the gap to 350 yards.

As we moved higher, the cover became even shorter and more sparse. Between us and the kudu there was just one decent-sized shrub left: a head-high blackhook 50 yards away, and Matheus signalled that we would try to reach this bush with our final move. By this point I had spent a lot of time watching the kudu bull in my binoculars, his spiral horns growing larger at every stage of the stalk. The thought of spooking the bull by trying to cross such a large open area had me on edge, but I had great faith in Matheus’s judgment and sense of timing.

The bull stretched his neck upward to reach some tender leaves higher in the acacia, the ivory tips of his horns practically reaching as far back as his hips. That was our cue. Matheus sprinted, bent over at the waist, and I did my best not to be too much of a liability in his wake. Huddled behind the leafless blackhook, both of us carefully raised our binoculars. The white chevron on the bull’s muzzle was pointed straight at us. Busted! We couldn’t be sure how much of our approach the bull had seen, but he clearly knew that something wasn’t right.

I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t been watching through binoculars, but the kudu bull took a couple of steps and simply vanished into the shadows of an acacia just below the crest of the hill. It’s a mystery to me how an animal that large can disappear into the smallest vestige of cover. By knowing just where to look I could make out a couple of his legs, but the stripes on his body, the long mane, and even his horns, merged invisibly with the branches of the acacia.

Luckily, the kudu cows had not seen us, and they continued to feed unperturbed towards the hidden bull. Matheus put his lips to my ear and whispered very softly. “We will wait for the cows to see if the bull will come to them.”

It’s probably just as well that I wasn’t wearing a watch, because time slowed to a standstill. We were afraid to move much, knowing that the bull was staring through the branches of his acacia, trying to pinpoint us hiding behind ours. I was able to watch the cows use their tongues and lips to methodically strip the leaves from one twig, then another, and another. Then on to the next branch. Then on to the next bush. Twig by twig, branch by branch, bush by bush, the cows s-l-o-w-l-y closed the distance to the bull.

Later, Matheus told me that we had spent over an hour waiting to see whether the bull would be calmed by the cows, or whether he would yield to his suspicions and sneak over the top of the hill.

Matheus’s worn Nikon binoculars began to look like an outgrowth of his eye sockets. His patience, focus, and persistence are unequalled. Then I saw Matheus tense. I dialed my scope to 8X, in wordless anticipation that I would be shooting from our current position, 300 yards from the kudu.

The instant that the bull stepped from behind the acacia and towards the approaching cows, Matheus planted the sticks and whispered urgently, “Put one anywhere in the front half and I will find him.” The bull turned his head to look down at us.

Despite the urgency in Matheus’s voice, time continued to run in slow motion for me. Having spent so many hours practicing with my Leupold varmint hunter reticle, and knowing that the scope was set on 8X, I found the bull’s vital triangle and automatically put its center halfway between the 200 and 300 yard crosshairs. I don’t even remember squeezing the trigger, but after the shot I worked the bolt and acquired the kudu in the scope without lifting the rifle from the sticks. The bull was stumbling but still on his feet, climbing the last few yards to the ridge top. I placed the crosshair on his left hip, trying to angle the bullet diagonally through his body, and fired again. Then the kudu went over the hill.

I quickly dialed my scope down to its lowest magnification in case I had to take a close followup shot. Matheus and I scrambled up the loose rocks to the summit. The kudu bull had lain down just over the crest. He staggered to his feet and I put a third bullet into his right shoulder, heart, and lungs at 40 yards. Matheus touched my arm and smiled. “No more shooting. He was finished with the first shot.”

Matheus was right. The first bullet destroyed the kudu bull’s lungs and lodged under the skin on the right shoulder, but without breaking the right leg. The second bullet entered high on the body just forward of the left rear leg, but skittered along the left side and was found stuck in a rib, never having done any serious damage. The last shot smashed the right front shoulder and exited under the left front leg.

As I was absorbed in admiring my hard-won kudu, Matheus pointed out that the bull had a “third horn” in the middle of his forehead, something that Matheus had only seen twice before. The “third horn” was no competition for the two majestic spirals, though, which measured 52-3/8” (133cm) and 52-6/8” (134cm) green.

It was an unforgettable hunt with a glorious trophy to preserve the memory!

The great size of the kudu, as well as the very rugged terrain, meant that that the photos had to be taken without moving the bull. Matheus didn’t like the two blackthorn acacias in the background, so he used his panga to remove both trees to provide the sweeping view of the rolling hills in the background that he thought the kudu deserved. Matheus never spared any effort on my behalf.

Before positioning the kudu for the photo session, Matheus pulled an inhaler from his pocket. Believe it or not, Matheus is allergic to kudu! From what I had observed over the past 2 days, I suspect that kudu are allergic to him, too. If not, they should be.

With the satisfying results of the morning’s hunt now preserved in my camera, we turned to the real work at hand. The bakkie was close to a half mile away, and on the other side of the hill. This 600-pound kudu didn’t look very portable to me. Thankfully, Matheus knew of a road on our side of the hill, at the bottom. Since Michael didn’t know the road network on the Erasmus farm, Matheus hiked back to the bakkie while Michael and I walked down to find the nearby road, marking the turnoff with an acacia branch. Matheus was able to crawl the bakkie right up to the kudu, and we soon had the bull shoehorned into the back.

My only regret was that the meat from my kudu belonged to the Erasmus farm, preventing me from enjoying one of my favorite meals – kudu steaks on the braai. The farm’s abatoir was very well-appointed, with a gambrel on an I-beam trolley system. Matheus, Michael, and 2 farm workers made short work of butchering my kudu while I handed out a fistful of R20 notes for the 2 recovered bullets.

Selma had packed us a picnic lunch – roast beef sandwiches, bananas, and guava – which we savored under a huge camelthorn acacia in Harry’s yard. After lunch, Matheus and Michael took a well-earned nap on the lawn, while I did some birdwatching on the grounds. It wasn’t long before Harry himself pulled up in his Toyota Hilux. He invited me in to his house, and I spent the next hour and a half learning about Harry’s cattle and sheep farm, as well as his former life as the CEO of Plastic Packaging (Ptd) Ltd, whose Oasis brand bottled water was ubiquitous across this thirsty land.

Our conversation changed gears when Matheus, now refreshed and anxious to get back out in the field, asked Harry about the possibility of taking a springbok ram. Harry and Matheus spoke in rapid-fire Afrikaans, gesturing with their hands to convey the geography. Matheus nodded his understanding, I shook Harry’s hand, we loaded the skull and horns of my kudu into the bakkie, and we were off.

We returned to the flat thornveld through which we had driven at sunrise. Matheus was in search of a particular old springbok ram, no longer holding a breeding territory, that was traveling with a small herd of 4 adolescent rams. Harry was familiar with this ram (PHs and farmers know many of their game animals as individuals), and we found the herd exactly where Harry had predicted that they would be. The stalk was on!

The blackhook acacia was spaced very closely, which made it easy for us to remain hidden from the springbok, but simultaneously it was difficult for us to keep track of the old ram amidst the herd. There was a brisk, steady wind from our left, and the herd was moving to our right, so we had to keep stalking parallel to the rams to avoid being upwind of them. The wind noise drowned out the sound of our walking. The springbok were not in a hurry, yet they covered a lot of ground during the 30 minutes that we followed them.

We got closer and closer, the rams completely unaware of us. Matheus picked up the pace, anticipating the rams’s path, planning to intercept them as they crossed a narrow shooting lane. We were nearly busted when a steenbok spurted out of the grass just ahead of us, crossing in front of the springbok. The springbok stopped and went on alert, swiveling their heads and twitching their tails nervously, but didn’t detect us.

As soon as the rams began walking again, Matheus positioned us ahead of the herd and set up the sticks. “I will tell you which one to shoot,” he whispered. I had the scope dialed all the way down, expecting the springbok to cross less than 100 yards in front of us. The first ram appeared, then another, and then the old ram with thick brown bases on his horns. Matheus said, “The third one.” The words were barely out of his mouth when I touched off the shot. The ram dropped instantly.

I hadn’t accounted properly for the strong wind, and the bullet had deflected a couple of inches to the right of my aim point, breaking the ram’s neck where it joined his body. But all’s well that ends well!

The sun was setting as the white crest flared on the old ram’s back. I took a deep draft of the vanilla-honey scent produced by the glands that run down the center of the crest – a classic safari experience in southern Africa, where springbok are the most abundant antelope.

In just 2 days of hunting, Matheus “The Magician” had conjured up all 3 of the trophy animals on my wish list. Now I was looking forward to some non-trophy hunting, and a few other wildlife-related activities.

A superb day of hunting was made complete by a dinner of David’s springbok steaks, masterfully seared over camelthorn coals by Claude. Smothered in Selma’s mushroom gravy, with potatoes and green beans on the side, I ate so many of the silver dollar-sized steaks that I barely had room for the puff pastry dessert.

Around the campfire, I found out that everyone else had a great day, too. Jacques had found Miguel’s kudu from yesterday, and David had collected a nice impala ram with his bow. Claude’s slow motion video (starting at 10:00 on the Delgado Safari) reveals the impala jumping David’s bowstring, but David held low enough that the arrow took the ram in the top of the lungs. That meant impala on the dinner table tomorrow!

Every hunter who dreams of Africa wants a trophy kudu. On my 2007 safari to Zimbabwe I had seen quite a few kudu cows and young bulls, but the several mature bulls that we saw melted into the mopane forest before I could get on the sticks.

I had some concerns about my prospects for kudu at Kowas, too. Kudu in Namibia have been suffering from a rabies epidemic, apparently spread from animal to animal via their saliva, gaining entry to their bloodstream through the thorn scratches in their mouths. It’s easy enough to imagine that any browser in Namibia would have a sore mouth – virtually every shrub and tree has thorns (see camelthorn photo below).

Matheus told me that 105 kudu skulls, nearly all of them from kudu killed by rabies, were found on the property adjacent to Kowas in the past year.

On the upside, Johnny (JGRaider) and Team Fet had collected some very fine kudu at Kowas recently, and even after just one day of hunting I had a great deal of confidence in Matheus’s ability to find and stalk game.

This morning was a carbon copy of yesterday’s – cold and clear, with the francolin wake-up call coming right on time. I bundled up in all the clothes that I had, wolfed down another rib-sticking breakfast, checked the scope power setting on my rifle, and met Matheus and Michael at the bakkie just before sunrise. Because David and Claude were bowhunting on the Kowas property again today, Matheus had planned our kudu hunt for another neighboring farm, belonging to Harry and Alta Erasmus, part of the 400,000 acre (>600 square miles) Dordabis Conservancy.

Unlike the Seifart farm, which is flat, the Erasmus farm had many rocky hills framing the central valley. Kudu love the acacia-covered hills, and we hoped to catch an old bull warming his bones in the early morning sun after a bitter night on the veld.

The Erasmus farm is only a few minutes away up the main gravel road (C23) from Kowas, but our bakkie was suffering from frost on the inside of the windscreen again. However, this time I was prepared. Matheus had shown me a few tricks in the field, so I returned the favor. I pulled a plastic hotel key card out of my backpack and neatly scraped clean my half of the windscreen and side window, producing a double handful of of ice shavings in a few seconds. Matheus laughed appreciatively, tossed his useless windscreen rag onto the dashboard, and employed the new tool to give himself a panoramic view of the road. That key card/ice scraper is now part of the bakkie’s kit.

Unfortunately, none of this cold-weather technology did Michael any good. He was stuck in the back of bakkie, freezing, again today. Luckily, by the time we got to the Erasmus farm gate the sun was painting the hillsides that gorgeous tangerine color that only seems to happen in Africa. Matheus and I climbed into the back of bakkie, while Michael took over the driving duties.

On the 2-track entering the farm we drove across the valley floor. We surprised a duiker, which panicked when it couldn’t find its usual hole through the cattle fence. After bouncing off the fence a few times, it see-sawed down the road a little farther, in that rocking horse gait peculiar to duikers, and ducked through the next hole.

Matheus pointed out the springbok rams defending their individual territories, creating an evenly spaced pattern of males, with the ewes wandering freely between territories. I didn’t know it at the time, but Matheus was already sizing up those springbok rams for a future hunt, making a mental note of the best trophies.

After crossing the valley, the 2-track climbed partway up the hill and then turned to contour along the hill about a hundred feet above the base. From our elevated vantage point we had a commanding view of the valley floor, and could see across to the hill on the opposite side of the valley. Giraffe browsed in the camelthorn savannah, and black wildebeest were frolicking in the open plain in a mixed herd with some springbok.

The 2-track on the hillside was tough going for the bakkie – very rutted and rocky. A bat-eared fox peered at us from the fenceline along the “road.” Much of the blackhook acacia on the hill appeared to be dead. Matheus confirmed that it had been poisoned by aerial herbicide application, to provide more moisture for the grass that the cattle use as forage. Indeed, the poisoned areas had much more abundant grass cover than the unsprayed patches. However, kudu are not grazers but browsers, and dislike sharing their habitat with cattle. Matheus said, “We must drive along the hill until we come to a place without cattle.”

We rattled along the 2-track for several miles, seeing quite a few kudu cows and calves, but no bulls. We crossed the valley and drove back along the flank of the hill on the other side of the valley.

Suddenly, Matheus tapped the top of the bakkie and whispered to Michael, “Stop behind the tree.” Michael parked the bakkie behind a camelthorn acacia growing right beside the road. Matheus whispered in my ear, “Kudu! A bull watching 2 cows.” He pointed to the crest of the hill 500 yards directly above us, where the two cows were silhouetted, feeding. The bull was 150 yards from the cows, just below the crest, dividing his time between watching them and pulling leaves off the acacias.

Matheus hopped out of the bakkie, using the tree for cover, and I handed him my rifle. As soon I was on the ground, Michael drove the bakkie out of sight. Matheus and I located the kudu bull in our binoculars. I didn’t know what Matheus was thinking, but I had looked at a lot of kudu photos in preparation for my safari, and this bull certainly looked plenty good enough to me!

Unfortunately for us, the kudu was not watching the departing bakkie. He was looking straight at us, or at least straight at the tree under which we were kneeling. As the minutes passed, Matheus never took his binoculars off the bull. When the bull finally turned his head to continue browsing, Matheus crouched down low, motioning for me to do likewise and stay close behind him. We quickly covered the 25 yards to a chest-high blackhook acacia without alarming the kudu bull, which continued to feed slowly towards the cows.

The hillside was covered with canteloupe-sized scree, which made the stalk more difficult. The rocks were unstable, and the ground was so dry that the acacias were mostly short and widely spaced. Every dash to the next bit of cover risked detection by the kudu. Nevertheless, thanks to Matheus, over the next half hour we made good progress, closing the gap to 350 yards.

As we moved higher, the cover became even shorter and more sparse. Between us and the kudu there was just one decent-sized shrub left: a head-high blackhook 50 yards away, and Matheus signalled that we would try to reach this bush with our final move. By this point I had spent a lot of time watching the kudu bull in my binoculars, his spiral horns growing larger at every stage of the stalk. The thought of spooking the bull by trying to cross such a large open area had me on edge, but I had great faith in Matheus’s judgment and sense of timing.

The bull stretched his neck upward to reach some tender leaves higher in the acacia, the ivory tips of his horns practically reaching as far back as his hips. That was our cue. Matheus sprinted, bent over at the waist, and I did my best not to be too much of a liability in his wake. Huddled behind the leafless blackhook, both of us carefully raised our binoculars. The white chevron on the bull’s muzzle was pointed straight at us. Busted! We couldn’t be sure how much of our approach the bull had seen, but he clearly knew that something wasn’t right.

I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t been watching through binoculars, but the kudu bull took a couple of steps and simply vanished into the shadows of an acacia just below the crest of the hill. It’s a mystery to me how an animal that large can disappear into the smallest vestige of cover. By knowing just where to look I could make out a couple of his legs, but the stripes on his body, the long mane, and even his horns, merged invisibly with the branches of the acacia.

Luckily, the kudu cows had not seen us, and they continued to feed unperturbed towards the hidden bull. Matheus put his lips to my ear and whispered very softly. “We will wait for the cows to see if the bull will come to them.”

It’s probably just as well that I wasn’t wearing a watch, because time slowed to a standstill. We were afraid to move much, knowing that the bull was staring through the branches of his acacia, trying to pinpoint us hiding behind ours. I was able to watch the cows use their tongues and lips to methodically strip the leaves from one twig, then another, and another. Then on to the next branch. Then on to the next bush. Twig by twig, branch by branch, bush by bush, the cows s-l-o-w-l-y closed the distance to the bull.

Later, Matheus told me that we had spent over an hour waiting to see whether the bull would be calmed by the cows, or whether he would yield to his suspicions and sneak over the top of the hill.

Matheus’s worn Nikon binoculars began to look like an outgrowth of his eye sockets. His patience, focus, and persistence are unequalled. Then I saw Matheus tense. I dialed my scope to 8X, in wordless anticipation that I would be shooting from our current position, 300 yards from the kudu.

The instant that the bull stepped from behind the acacia and towards the approaching cows, Matheus planted the sticks and whispered urgently, “Put one anywhere in the front half and I will find him.” The bull turned his head to look down at us.

Despite the urgency in Matheus’s voice, time continued to run in slow motion for me. Having spent so many hours practicing with my Leupold varmint hunter reticle, and knowing that the scope was set on 8X, I found the bull’s vital triangle and automatically put its center halfway between the 200 and 300 yard crosshairs. I don’t even remember squeezing the trigger, but after the shot I worked the bolt and acquired the kudu in the scope without lifting the rifle from the sticks. The bull was stumbling but still on his feet, climbing the last few yards to the ridge top. I placed the crosshair on his left hip, trying to angle the bullet diagonally through his body, and fired again. Then the kudu went over the hill.

I quickly dialed my scope down to its lowest magnification in case I had to take a close followup shot. Matheus and I scrambled up the loose rocks to the summit. The kudu bull had lain down just over the crest. He staggered to his feet and I put a third bullet into his right shoulder, heart, and lungs at 40 yards. Matheus touched my arm and smiled. “No more shooting. He was finished with the first shot.”

Matheus was right. The first bullet destroyed the kudu bull’s lungs and lodged under the skin on the right shoulder, but without breaking the right leg. The second bullet entered high on the body just forward of the left rear leg, but skittered along the left side and was found stuck in a rib, never having done any serious damage. The last shot smashed the right front shoulder and exited under the left front leg.

As I was absorbed in admiring my hard-won kudu, Matheus pointed out that the bull had a “third horn” in the middle of his forehead, something that Matheus had only seen twice before. The “third horn” was no competition for the two majestic spirals, though, which measured 52-3/8” (133cm) and 52-6/8” (134cm) green.

It was an unforgettable hunt with a glorious trophy to preserve the memory!

The great size of the kudu, as well as the very rugged terrain, meant that that the photos had to be taken without moving the bull. Matheus didn’t like the two blackthorn acacias in the background, so he used his panga to remove both trees to provide the sweeping view of the rolling hills in the background that he thought the kudu deserved. Matheus never spared any effort on my behalf.

Before positioning the kudu for the photo session, Matheus pulled an inhaler from his pocket. Believe it or not, Matheus is allergic to kudu! From what I had observed over the past 2 days, I suspect that kudu are allergic to him, too. If not, they should be.

With the satisfying results of the morning’s hunt now preserved in my camera, we turned to the real work at hand. The bakkie was close to a half mile away, and on the other side of the hill. This 600-pound kudu didn’t look very portable to me. Thankfully, Matheus knew of a road on our side of the hill, at the bottom. Since Michael didn’t know the road network on the Erasmus farm, Matheus hiked back to the bakkie while Michael and I walked down to find the nearby road, marking the turnoff with an acacia branch. Matheus was able to crawl the bakkie right up to the kudu, and we soon had the bull shoehorned into the back.

My only regret was that the meat from my kudu belonged to the Erasmus farm, preventing me from enjoying one of my favorite meals – kudu steaks on the braai. The farm’s abatoir was very well-appointed, with a gambrel on an I-beam trolley system. Matheus, Michael, and 2 farm workers made short work of butchering my kudu while I handed out a fistful of R20 notes for the 2 recovered bullets.

Selma had packed us a picnic lunch – roast beef sandwiches, bananas, and guava – which we savored under a huge camelthorn acacia in Harry’s yard. After lunch, Matheus and Michael took a well-earned nap on the lawn, while I did some birdwatching on the grounds. It wasn’t long before Harry himself pulled up in his Toyota Hilux. He invited me in to his house, and I spent the next hour and a half learning about Harry’s cattle and sheep farm, as well as his former life as the CEO of Plastic Packaging (Ptd) Ltd, whose Oasis brand bottled water was ubiquitous across this thirsty land.

Our conversation changed gears when Matheus, now refreshed and anxious to get back out in the field, asked Harry about the possibility of taking a springbok ram. Harry and Matheus spoke in rapid-fire Afrikaans, gesturing with their hands to convey the geography. Matheus nodded his understanding, I shook Harry’s hand, we loaded the skull and horns of my kudu into the bakkie, and we were off.

We returned to the flat thornveld through which we had driven at sunrise. Matheus was in search of a particular old springbok ram, no longer holding a breeding territory, that was traveling with a small herd of 4 adolescent rams. Harry was familiar with this ram (PHs and farmers know many of their game animals as individuals), and we found the herd exactly where Harry had predicted that they would be. The stalk was on!

The blackhook acacia was spaced very closely, which made it easy for us to remain hidden from the springbok, but simultaneously it was difficult for us to keep track of the old ram amidst the herd. There was a brisk, steady wind from our left, and the herd was moving to our right, so we had to keep stalking parallel to the rams to avoid being upwind of them. The wind noise drowned out the sound of our walking. The springbok were not in a hurry, yet they covered a lot of ground during the 30 minutes that we followed them.

We got closer and closer, the rams completely unaware of us. Matheus picked up the pace, anticipating the rams’s path, planning to intercept them as they crossed a narrow shooting lane. We were nearly busted when a steenbok spurted out of the grass just ahead of us, crossing in front of the springbok. The springbok stopped and went on alert, swiveling their heads and twitching their tails nervously, but didn’t detect us.

As soon as the rams began walking again, Matheus positioned us ahead of the herd and set up the sticks. “I will tell you which one to shoot,” he whispered. I had the scope dialed all the way down, expecting the springbok to cross less than 100 yards in front of us. The first ram appeared, then another, and then the old ram with thick brown bases on his horns. Matheus said, “The third one.” The words were barely out of his mouth when I touched off the shot. The ram dropped instantly.

I hadn’t accounted properly for the strong wind, and the bullet had deflected a couple of inches to the right of my aim point, breaking the ram’s neck where it joined his body. But all’s well that ends well!

The sun was setting as the white crest flared on the old ram’s back. I took a deep draft of the vanilla-honey scent produced by the glands that run down the center of the crest – a classic safari experience in southern Africa, where springbok are the most abundant antelope.

In just 2 days of hunting, Matheus “The Magician” had conjured up all 3 of the trophy animals on my wish list. Now I was looking forward to some non-trophy hunting, and a few other wildlife-related activities.

A superb day of hunting was made complete by a dinner of David’s springbok steaks, masterfully seared over camelthorn coals by Claude. Smothered in Selma’s mushroom gravy, with potatoes and green beans on the side, I ate so many of the silver dollar-sized steaks that I barely had room for the puff pastry dessert.

Around the campfire, I found out that everyone else had a great day, too. Jacques had found Miguel’s kudu from yesterday, and David had collected a nice impala ram with his bow. Claude’s slow motion video (starting at 10:00 on the Delgado Safari) reveals the impala jumping David’s bowstring, but David held low enough that the arrow took the ram in the top of the lungs. That meant impala on the dinner table tomorrow!

Last edited by a moderator:

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

8 July 2014

With the oryx, kudu, and springbok trophies in the salt, I didn’t rise with francolins this morning. When I had booked my safari almost a year before, I chose the “First African Safari” package from Kowas, which included the 3 species I had already collected, plus a blue wildebeest. At the time, I asked Ansie to substitute a black wildebeest for the blue, but in the several weeks leading up to my hunt I had decided that I only wanted to bring home the oryx, kudu, and springbok.

So, after a leisurely breakfast, I met Matheus and Michael at 0730 for some non-trophy hunting. The day’s agenda was up to Matheus. I couldn’t have been in more capable hands.

It was another cool, cloudless day, but at least the sun was up when we boarded the bakkie. Ansie had mended a blackhook thorn tear in my down vest, so I was quite comfortable in the seat next to Matheus, who was probably wearing every piece of clothing that he owns in an attempt to stay warm.

Matheus explained the plan for the morning hunt. “A local landowner needs meat for her workers. She has 3 oryx on a culling license. We will stalk them if possible, but be ready to shoot from the bakkie, also. We will pick up one of her farm workers to show us where the oryx are. The worker will expect you to shoot any oryx that we find.”

The farm owned by Ms. Pashukeni Shoombe is just a few minutes up the C23 from Kowas. A farm worker in a blue-green jumpsuit ran to open the gate for us. Ms. Shoombe, wearing a cheery yellow print dress, came out of the house to greet us, and to assure us that the farm guard dog – a black shar-pei – was harmless as well as ugly. Ms. Shoombe said, “I am very happy to have you hunting on my property. Without game meat for my workers, I will have to go to the butcher in Windhoek, which is very expensive.”

The importance of meat in the African diet cannot be overstated. In Namibia the Damara-Nama have an adage: “Without meat there is no food.” If you have read Ruark and Bell, you are well aware of the hunter’s obligation to provide an abundance of meat for the camp. Matheus related to me the Oshiwambo superstition that eating too much beef would make the legs swell – only game meat for him and his people!

I later found out much more about Ms. Shoombe, who is a major figure in Namibian politics. She was a commander in the SWAPO army (PLAN) that won independence for Namibia in 1990. She was elected as a member of the first Namibian parliament which wrote the country’s constitution, stipulating conservation of wildlife as a national priority. More than 40% of Namibia is now under conservation management, up from 13% at the time of independence. I saw Ms. Shoombe's photo in the Independence Museum in Windhoek. Nothing about her modest demeanor would suggest that she is a hero in modern Namibia.

Remarkably, Pashukeni Shoombe and Danie Strauss had been on opposing sides in a shooting war less than 30 years ago, and yet now are neighbors on the friendliest of terms. Namibia has a fascinating history full of interesting people, and I look forward to learning more about its successful reconciliation after the bitter, protracted war between SWAPO and the South African Defense Forces.

Ms. Shoombe’s farm was thick with blackhook acacia roughly 10 feet tall, making it difficult to locate game from the elevated seats in the back of bakkie, where Matheus and I were riding. Michael crawled the bakkie around the farm’s perimeter road, a 2-track in deep red Kalahari sand. The farm was home to many steenbok, pairs of them looking up at us from the long grass.

Michael spotted the herd of a dozen oryx from the driver’s seat. From his vantage point he could see under the crowns of the acacias. The wind was at our back, guaranteed to make any stalk a challenge. Michael dropped Matheus and me behind an acacia, and drove the bakkie away, hoping to distract the oryx while Matheus and I moved to a more favorable position relative to the wind. The strategy worked. Hunkered down behind a blackhook, Matheus and I could see the oryx swivel their heads to follow the clattering bakkie.

Matheus knew that the oryx would soon wind us. He set up the sticks with the legs spread wide so that I could shoot from the sitting position. The oryx were only about 100 yards away, but the tall grass and dense thornveld obscured most of them. With my rifle in the sticks, I scanned with my scope along the line of oryx until I came to the last one. Although most of the animal was behind a tangle of branches, I had an clear line of sight to the vitals. I threaded my shot through the branches.

The oryx cow was quartering towards me. The bullet drove a 2-inch section of rib into the left lung, exiting on the right side through the liver, leaving the gall bladder hanging outside the oryx’s body. Despite the lethal damage, the oryx upheld the reputation for toughness, running almost 300 yards before collapsing. Matheus had no trouble following the blood trail from the pass-through wound channel.

We stopped by the Shoombe house to drop off the farm worker. Ms. Shoombe came out to see the oryx. She was thrilled with our success, and warmly invited us back. We readily agreed, and made plans for an afternoon hunt.

Appropriately, Selma had whipped up a tasty lunch of pasta with oryx meat sauce for lunch. After lunch I did some birdwatching at the Kowas lodge waterhole, seeing my first long-tailed paradise wydah and red-billed wood hoopoe. A duiker, a family of warthogs, and a yellow mongoose came in for a drink.

At 1500 Matheus and Michael picked me up for the return trip the Shoombe farm, hoping to catch the oryx herd coming out of the rocky hills to drink at the farm’s waterhole. As before, we picked up a farmhand to show us around. As we circumnavigated the perimeter road we looked for fresh oryx tracks on top of our tire tracks from the morning.

We had just cut a fresh track and were preparing to start a stalk when an oryx cow bolted from the farm’s thornveld and slipped under the fence, headed for the hills. A 2-year-old bull was right behind her, but missed the hole under the fence. He turned in our direction, momentarily confused. It only took a second for me to unfold the legs of my bipod for a shot from the roof of the bakkie. At 90 yards the bullet took the oryx in the center of the chest, breaking his spine where it dips low at the neck-body junction, tearing up the lungs and large blood vessels on top of the heart, and penetrating to the center of the rumen filled with undigested wet grass, where Michael later found the perfectly mushroomed Barnes TSX.

I assumed that after loading the oryx into the bakkie we would drive back to Kowas to butcher it, but Matheus was ready for more hunting. It wasn’t long before he found the herd near where we had shot the oryx cow that morning. The wind was still behind us, so the oryx spooked as soon as we were out of the bakkie. Matheus led the stalk, circling the oryx to prevent them from scenting us. Of course, they were on high alert, with every pair of eyes looking over their shoulders. But the thick blackhook allowed us to stay hidden, and the soft sourgrass made our stalk nearly silent.

We caught up to them within 20 minutes. Matheus worked us in very close – no more than 75 yards. I don’t think that the oryx knew that we were there, but they were all turned towards us, watching their backtrail. Matheus placed the sticks at the edge of an acacia. When I looked through the scope I didn’t have a clear shooting lane. The branches in front of us were partially obscuring the herd, but without being able to focus on the near branches I couldn’t be sure of a clean shot. I whispered to Matheus, but he replied, “Take the shot. If I move the sticks the oryx will see us.”

At this range I had no trouble getting a steady hold on the center of an oryx’s chest. The crosshairs looked perfect when I squeezed the trigger. But there was no sound of a bullet impact, and the herd lit the afterburners. We searched for signs of hit, but found no blood or hair. I can only assume that my bullet hit a branch somewhere close to the muzzle.

Still, we had collected 2 oryx for Ms. Shoombe today, and could look forward to a supper of springbok cordon bleu, courtesy of David’s excellent bowmanship and Selma’s kitchen craft.

With the oryx, kudu, and springbok trophies in the salt, I didn’t rise with francolins this morning. When I had booked my safari almost a year before, I chose the “First African Safari” package from Kowas, which included the 3 species I had already collected, plus a blue wildebeest. At the time, I asked Ansie to substitute a black wildebeest for the blue, but in the several weeks leading up to my hunt I had decided that I only wanted to bring home the oryx, kudu, and springbok.

So, after a leisurely breakfast, I met Matheus and Michael at 0730 for some non-trophy hunting. The day’s agenda was up to Matheus. I couldn’t have been in more capable hands.

It was another cool, cloudless day, but at least the sun was up when we boarded the bakkie. Ansie had mended a blackhook thorn tear in my down vest, so I was quite comfortable in the seat next to Matheus, who was probably wearing every piece of clothing that he owns in an attempt to stay warm.

Matheus explained the plan for the morning hunt. “A local landowner needs meat for her workers. She has 3 oryx on a culling license. We will stalk them if possible, but be ready to shoot from the bakkie, also. We will pick up one of her farm workers to show us where the oryx are. The worker will expect you to shoot any oryx that we find.”

The farm owned by Ms. Pashukeni Shoombe is just a few minutes up the C23 from Kowas. A farm worker in a blue-green jumpsuit ran to open the gate for us. Ms. Shoombe, wearing a cheery yellow print dress, came out of the house to greet us, and to assure us that the farm guard dog – a black shar-pei – was harmless as well as ugly. Ms. Shoombe said, “I am very happy to have you hunting on my property. Without game meat for my workers, I will have to go to the butcher in Windhoek, which is very expensive.”

The importance of meat in the African diet cannot be overstated. In Namibia the Damara-Nama have an adage: “Without meat there is no food.” If you have read Ruark and Bell, you are well aware of the hunter’s obligation to provide an abundance of meat for the camp. Matheus related to me the Oshiwambo superstition that eating too much beef would make the legs swell – only game meat for him and his people!

I later found out much more about Ms. Shoombe, who is a major figure in Namibian politics. She was a commander in the SWAPO army (PLAN) that won independence for Namibia in 1990. She was elected as a member of the first Namibian parliament which wrote the country’s constitution, stipulating conservation of wildlife as a national priority. More than 40% of Namibia is now under conservation management, up from 13% at the time of independence. I saw Ms. Shoombe's photo in the Independence Museum in Windhoek. Nothing about her modest demeanor would suggest that she is a hero in modern Namibia.

Remarkably, Pashukeni Shoombe and Danie Strauss had been on opposing sides in a shooting war less than 30 years ago, and yet now are neighbors on the friendliest of terms. Namibia has a fascinating history full of interesting people, and I look forward to learning more about its successful reconciliation after the bitter, protracted war between SWAPO and the South African Defense Forces.

Ms. Shoombe’s farm was thick with blackhook acacia roughly 10 feet tall, making it difficult to locate game from the elevated seats in the back of bakkie, where Matheus and I were riding. Michael crawled the bakkie around the farm’s perimeter road, a 2-track in deep red Kalahari sand. The farm was home to many steenbok, pairs of them looking up at us from the long grass.

Michael spotted the herd of a dozen oryx from the driver’s seat. From his vantage point he could see under the crowns of the acacias. The wind was at our back, guaranteed to make any stalk a challenge. Michael dropped Matheus and me behind an acacia, and drove the bakkie away, hoping to distract the oryx while Matheus and I moved to a more favorable position relative to the wind. The strategy worked. Hunkered down behind a blackhook, Matheus and I could see the oryx swivel their heads to follow the clattering bakkie.

Matheus knew that the oryx would soon wind us. He set up the sticks with the legs spread wide so that I could shoot from the sitting position. The oryx were only about 100 yards away, but the tall grass and dense thornveld obscured most of them. With my rifle in the sticks, I scanned with my scope along the line of oryx until I came to the last one. Although most of the animal was behind a tangle of branches, I had an clear line of sight to the vitals. I threaded my shot through the branches.

The oryx cow was quartering towards me. The bullet drove a 2-inch section of rib into the left lung, exiting on the right side through the liver, leaving the gall bladder hanging outside the oryx’s body. Despite the lethal damage, the oryx upheld the reputation for toughness, running almost 300 yards before collapsing. Matheus had no trouble following the blood trail from the pass-through wound channel.

We stopped by the Shoombe house to drop off the farm worker. Ms. Shoombe came out to see the oryx. She was thrilled with our success, and warmly invited us back. We readily agreed, and made plans for an afternoon hunt.

Appropriately, Selma had whipped up a tasty lunch of pasta with oryx meat sauce for lunch. After lunch I did some birdwatching at the Kowas lodge waterhole, seeing my first long-tailed paradise wydah and red-billed wood hoopoe. A duiker, a family of warthogs, and a yellow mongoose came in for a drink.

At 1500 Matheus and Michael picked me up for the return trip the Shoombe farm, hoping to catch the oryx herd coming out of the rocky hills to drink at the farm’s waterhole. As before, we picked up a farmhand to show us around. As we circumnavigated the perimeter road we looked for fresh oryx tracks on top of our tire tracks from the morning.

We had just cut a fresh track and were preparing to start a stalk when an oryx cow bolted from the farm’s thornveld and slipped under the fence, headed for the hills. A 2-year-old bull was right behind her, but missed the hole under the fence. He turned in our direction, momentarily confused. It only took a second for me to unfold the legs of my bipod for a shot from the roof of the bakkie. At 90 yards the bullet took the oryx in the center of the chest, breaking his spine where it dips low at the neck-body junction, tearing up the lungs and large blood vessels on top of the heart, and penetrating to the center of the rumen filled with undigested wet grass, where Michael later found the perfectly mushroomed Barnes TSX.

I assumed that after loading the oryx into the bakkie we would drive back to Kowas to butcher it, but Matheus was ready for more hunting. It wasn’t long before he found the herd near where we had shot the oryx cow that morning. The wind was still behind us, so the oryx spooked as soon as we were out of the bakkie. Matheus led the stalk, circling the oryx to prevent them from scenting us. Of course, they were on high alert, with every pair of eyes looking over their shoulders. But the thick blackhook allowed us to stay hidden, and the soft sourgrass made our stalk nearly silent.

We caught up to them within 20 minutes. Matheus worked us in very close – no more than 75 yards. I don’t think that the oryx knew that we were there, but they were all turned towards us, watching their backtrail. Matheus placed the sticks at the edge of an acacia. When I looked through the scope I didn’t have a clear shooting lane. The branches in front of us were partially obscuring the herd, but without being able to focus on the near branches I couldn’t be sure of a clean shot. I whispered to Matheus, but he replied, “Take the shot. If I move the sticks the oryx will see us.”

At this range I had no trouble getting a steady hold on the center of an oryx’s chest. The crosshairs looked perfect when I squeezed the trigger. But there was no sound of a bullet impact, and the herd lit the afterburners. We searched for signs of hit, but found no blood or hair. I can only assume that my bullet hit a branch somewhere close to the muzzle.

Still, we had collected 2 oryx for Ms. Shoombe today, and could look forward to a supper of springbok cordon bleu, courtesy of David’s excellent bowmanship and Selma’s kitchen craft.

Last edited by a moderator:

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2010

- Messages

- 15,809

- Reaction score

- 50,485

- Location

- Zambia

- Website

- www.takerireservezambia.com

- Deals & offers

- 25

- Media

- 359

- Articles

- 24

- Member of

- sci int,wpaz, PGOAZ

- Hunted

- zambia, tanzania, zimbabwe,Mozambique ,hungary, france, england

toby an interesting write up thanks

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

Hi Mike. Glad you're enjoying it!

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

9 July 2014

Miguel and David took a day off from hunting to see the sights in Windhoek, giving me my first chance to hunt the Kowas farm. Although the hunting had been excellent on the Seifart, Erasmus, and Shoombe farms, there is no comparison to Kowas in terms of sheer abundance and variety of game. The lack of cattle on Kowas benefits wildlife tremendously.

Matheus suggested that we hunt a non-trophy wildebeest. Danie’s management scheme targets barren cows, young cows with a narrow horn spread, and broken-horned bulls. Listening to Matheus detailing today’s search image, I realized that the correct identification of a non-trophy requires just as much of the PH’s knowledge as does the judgment of trophy animals.

Matheus found the first herd of about 20 blue wildebeest in some thick blackhook acacia. We drove about a mile past them and stalked back, the brisk wind coming from our right. Between the clumps of grass were the dried remains of “noisemaker” plants that crunched loudly underfoot and had to be carefully avoided, as blue wildebeest have keen hearing.

When we got within 100 yards, Matheus whispered, “Stay very close behind me, and shoot quickly once you are on the sticks. These blue wildebeest are very clever and will not stand still for long.” I nodded and verified that my scope power was set as low as it would go.

As we knelt behind a blackhook, the wildebeest all turned their heads and looked directly at us. One of the wildebeest began to snort loudly, and it wasn’t long before they thundered off. I thought that the crosswind my have swirled some of our scent to them, but Matheus explained, “They heard us whispering. These wildebeest have been hunted many times for non-trophy animals.” Matheus called Michael on the radio and he brought the bakkie around.

Matheus briefly considered looking for non-trophy springbok or oryx, but decided that he wanted to give me another chance at blue wildbeest. By now it was 0930 and warming quickly, so he directed Michael to drive to a known bedding area. The sourgrass was flattened in a 30-foot radius under the camelthorns, but there were no wildebeest and no fresh sign. Matheus said, “If they are not here then I know where they must go.” I had every reason to trust his intimate knowledge of the game.

Sure enough, the blue wildebeest herd was exactly where Matheus had predicted. We began our stalk, with plenty of blackhook for cover. We were nearly busted twice – first by a limping duiker ewe followed by her ram and lamb. They went by in single file less than 10 yards away without seeing or smelling us. More problematic were the three ostriches that clearly spotted us, with the sharpest eyes on the veld, and with necks long enough to see over the low thornbushes. They hastened off, which alerted but did not alarm the two dozen blue wildebeest.

Following the ostrich’s lead, the wildebeest turned to look in our direction. Matheus slowly but deliberately moved the sticks to the very edge of the blackhook and checked that my bullet path would be uncluttered by branches (no doubt remembering my deflected shot from yesterday), while still concealing us as much as possible. He whispered, “Do you see the two cows together? Take the one on the right.”

I turned up my scope to 6x for the 150-yard shot. The 2-year-old cow was quartering towards us, so I held a little below the point of her left shoulder. The bullet hit exactly where I was aiming, producing the welcome sound of a solid impact in the boiler room. At the shot the herd bolted in a cloud of dust. I lost sight of the cow, but Matheus had her in his binoculars and said, “She’s down.” She had run less than 200 yards.

A closer inspection at the skinning shed showed that the bullet entered just inside and slightly below the shoulder, taking out the top of the heart and part of both lungs before tearing up the liver and exiting.

The excitement of the stalk now over, I began thinking of the wildebeest tenderloin Stroganoff that Selma would be making – by request – for dinner tomorrow!

Thinking that our morning hunt was finished, I was surprised when Matheus had Michael drop us off to make a speculative stalk for the first herd of blue wildebeest that we had spooked. Matheus is absolutely relentless, and apparently likes a challenge! Michael pointed the bakkie back towards the skinning shed to drop off the young wildebeest cow, leaving Matheus and me to walk down the 2-track for the next 45 minutes scouring the blackhook scrub for the hypervigilant blue wildebeest.

We came across a small herd of black wildebeest gamboling on the veld, white tails swishing as they frolicked, in a mixed herd with mountain zebra and (unfortunately) ostrich, about 250 yards away. The ostrich saw us instantly and legged it for the horizon with the zebra close behind, leaving a dust cloud in their wake. The blue wildebeest were another 500 yards deeper in the bush, but wasted no time when they got the word from the other animals, spinning into the wind and sprinting out of sight. Matheus shrugged his shoulders. “I know where we can look for oryx and springbok on the way home,” he said cheerfully.

We came across a lonely old barren springbok ewe, but she high-stepped away when we stopped the bakkie for a look. We should have driven past and started a stalk from a half-mile out. But Selma’s fried chicken lunch (one of the very few domesticated animals on the menu so far) was calling our names.

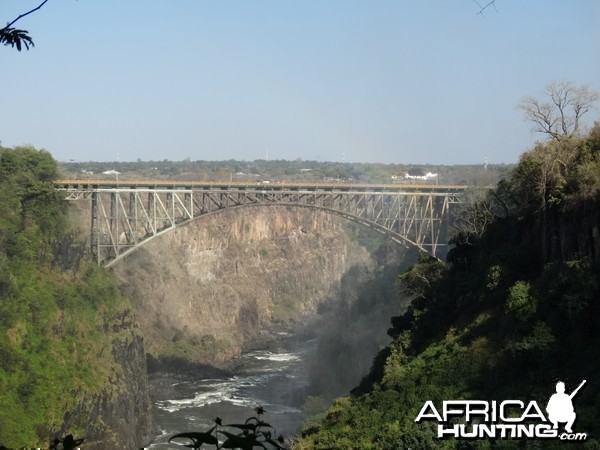

Early in the afternoon, my wife, Moira, and our two friends, Lucy and Paul, arrived at Kowas following their exploration of Victoria Falls (Zambia side) and Chobe (Botswana). Lucy and Paul had even bungee jumped off the Zambezi River bridge connecting Zambia and Zimbabwe!

We went on an afternoon game drive to show off the Kowas farm. When we returned for a dinner of chicken-fried impala steaks and gravy, we found that Danie had made it back from Madagascar with the good news that the Namibian National Rugby Team, the Welwitschias, had qualified for the World Cup!

Miguel and David took a day off from hunting to see the sights in Windhoek, giving me my first chance to hunt the Kowas farm. Although the hunting had been excellent on the Seifart, Erasmus, and Shoombe farms, there is no comparison to Kowas in terms of sheer abundance and variety of game. The lack of cattle on Kowas benefits wildlife tremendously.

Matheus suggested that we hunt a non-trophy wildebeest. Danie’s management scheme targets barren cows, young cows with a narrow horn spread, and broken-horned bulls. Listening to Matheus detailing today’s search image, I realized that the correct identification of a non-trophy requires just as much of the PH’s knowledge as does the judgment of trophy animals.

Matheus found the first herd of about 20 blue wildebeest in some thick blackhook acacia. We drove about a mile past them and stalked back, the brisk wind coming from our right. Between the clumps of grass were the dried remains of “noisemaker” plants that crunched loudly underfoot and had to be carefully avoided, as blue wildebeest have keen hearing.

When we got within 100 yards, Matheus whispered, “Stay very close behind me, and shoot quickly once you are on the sticks. These blue wildebeest are very clever and will not stand still for long.” I nodded and verified that my scope power was set as low as it would go.

As we knelt behind a blackhook, the wildebeest all turned their heads and looked directly at us. One of the wildebeest began to snort loudly, and it wasn’t long before they thundered off. I thought that the crosswind my have swirled some of our scent to them, but Matheus explained, “They heard us whispering. These wildebeest have been hunted many times for non-trophy animals.” Matheus called Michael on the radio and he brought the bakkie around.

Matheus briefly considered looking for non-trophy springbok or oryx, but decided that he wanted to give me another chance at blue wildbeest. By now it was 0930 and warming quickly, so he directed Michael to drive to a known bedding area. The sourgrass was flattened in a 30-foot radius under the camelthorns, but there were no wildebeest and no fresh sign. Matheus said, “If they are not here then I know where they must go.” I had every reason to trust his intimate knowledge of the game.

Sure enough, the blue wildebeest herd was exactly where Matheus had predicted. We began our stalk, with plenty of blackhook for cover. We were nearly busted twice – first by a limping duiker ewe followed by her ram and lamb. They went by in single file less than 10 yards away without seeing or smelling us. More problematic were the three ostriches that clearly spotted us, with the sharpest eyes on the veld, and with necks long enough to see over the low thornbushes. They hastened off, which alerted but did not alarm the two dozen blue wildebeest.

Following the ostrich’s lead, the wildebeest turned to look in our direction. Matheus slowly but deliberately moved the sticks to the very edge of the blackhook and checked that my bullet path would be uncluttered by branches (no doubt remembering my deflected shot from yesterday), while still concealing us as much as possible. He whispered, “Do you see the two cows together? Take the one on the right.”

I turned up my scope to 6x for the 150-yard shot. The 2-year-old cow was quartering towards us, so I held a little below the point of her left shoulder. The bullet hit exactly where I was aiming, producing the welcome sound of a solid impact in the boiler room. At the shot the herd bolted in a cloud of dust. I lost sight of the cow, but Matheus had her in his binoculars and said, “She’s down.” She had run less than 200 yards.

A closer inspection at the skinning shed showed that the bullet entered just inside and slightly below the shoulder, taking out the top of the heart and part of both lungs before tearing up the liver and exiting.

The excitement of the stalk now over, I began thinking of the wildebeest tenderloin Stroganoff that Selma would be making – by request – for dinner tomorrow!

Thinking that our morning hunt was finished, I was surprised when Matheus had Michael drop us off to make a speculative stalk for the first herd of blue wildebeest that we had spooked. Matheus is absolutely relentless, and apparently likes a challenge! Michael pointed the bakkie back towards the skinning shed to drop off the young wildebeest cow, leaving Matheus and me to walk down the 2-track for the next 45 minutes scouring the blackhook scrub for the hypervigilant blue wildebeest.

We came across a small herd of black wildebeest gamboling on the veld, white tails swishing as they frolicked, in a mixed herd with mountain zebra and (unfortunately) ostrich, about 250 yards away. The ostrich saw us instantly and legged it for the horizon with the zebra close behind, leaving a dust cloud in their wake. The blue wildebeest were another 500 yards deeper in the bush, but wasted no time when they got the word from the other animals, spinning into the wind and sprinting out of sight. Matheus shrugged his shoulders. “I know where we can look for oryx and springbok on the way home,” he said cheerfully.

We came across a lonely old barren springbok ewe, but she high-stepped away when we stopped the bakkie for a look. We should have driven past and started a stalk from a half-mile out. But Selma’s fried chicken lunch (one of the very few domesticated animals on the menu so far) was calling our names.

Early in the afternoon, my wife, Moira, and our two friends, Lucy and Paul, arrived at Kowas following their exploration of Victoria Falls (Zambia side) and Chobe (Botswana). Lucy and Paul had even bungee jumped off the Zambezi River bridge connecting Zambia and Zimbabwe!

We went on an afternoon game drive to show off the Kowas farm. When we returned for a dinner of chicken-fried impala steaks and gravy, we found that Danie had made it back from Madagascar with the good news that the Namibian National Rugby Team, the Welwitschias, had qualified for the World Cup!

Last edited by a moderator:

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

10 July 2014

The weather has returned to normal – chilly, but not freezing, in the morning, and very pleasant in the afternoon. The sky was clear blue, and we would spend more than two weeks in Namibia before seeing our first cloud!

One of the reasons that I chose Kowas for my safari is that Ansie assured me that my non-hunting wife and friends would have many activities from which to choose. We took advantage of that, asking Matheus to lead the four of us on a morning bush walk, starting from the Kowas lodge and climbing the “mountain” to the summit overlooking the Kudu Waterhole. The windblown Kalahari sand captures animal tracks beautifully. Matheus pointed out the difference between mountain zebra and plains zebra prints. We saw where a mother leopard and her offspring had used the road as a travel route in the night.

Genets, jackals, and snakes all had left their distinctive spoor. There was plenty of wildlife to be viewed, as well: steenbok, duiker, springbok, impala, blue wildebeest, and kudu. Matheus schooled us on the plants, including a tree whose bark the kudu eat to rid themselves of intestinal parasites.

From the top of the mountain, we could see much of the Kowas farm. There was camelthorn savanna where the soils were deep, and a band of short blackhook thornveld where the limestone was close to the surface and the soil shallow.

Looking down at the Kudu Waterhole, we saw a herd of impala, including a ram with a broken horn – perhaps a future non-trophy prospect! A very impressive warthog boar came in for a drink, sporting a long and thick left tusk.

Selma had whipped up a dish of impala lasagne for lunch. Danie generously spent a few hours with us, helping us plan our visit to Etosha, which would follow our stay at Kowas.

Moira, Lucy, and Paul had never been on a big game hunt, so at 1500 we met Matheus and Michael to look for a third non-trophy oryx at the Shoombe farm. The back of the bakkie was packed with people. The little diesel struggled gamely under the load. We picked up a worker at the Shoombe house and began circling the farm on the soft sandy roads, ducking and dodging the low-hanging blackhook and camelthorn branches. Michael did a superb job of maneuvering the bakkie to keep us from losing an eye to a thorn.

Matheus spotted a lone oryx bull (“by the light shining on his horns,” he later told us) bedded down in the long grass at the base of a blackhook acacia. The bull was too close to the road to let everyone join the stalk, so Michael dropped Matheus and me and drove away. We knelt for several minutes to verify that the oryx was focused on the departing bakkie, then moved from bush to bush as long as the oryx’s head was turned. At 95 yards Matheus set up the sticks. The oryx got to his feet to stare at us, but I already had the crosshairs on the point of his right shoulder to make the quartering shot, and was able to shoot quickly before he ran. The shooting lane to the oryx was completely unobstructed by brush – a rarity on this safari. The bullet broke the right shoulder and shredded the vessels at the top of the heart. The oryx stumbled 10 yards, crashed into a camelthorn acacia, and toppled onto his right side.

When Matheus and I reached the oryx the hair was rising on his body, but only on the front third. Matheus pointed out that there was no exit wound, and said that the bullet would be found under skin just at the point where the hair had failed to rise. He touched the point of his knife blade to that spot and the 4-petaled Barnes copper flower popped out into his fingers!

Moira, Lucy, and Paul were impressed by the size and beauty of the oryx, and the respect with which he was treated. I think that most hunters appreciate the seamless connection between the planning, the stalk, the kill, and the meat at the table. But for non-hunters, the idea that dinner was roaming the veld just a few hours before is something of a revelation, and is in stark contrast to the rearing and slaughter of domesticated animals, or the purchase of shrink-wrapped meat at the grocery store.

We watched Matheus, Michael, and Timo skin and butcher the 550-pound oryx with orchestrated precision – never a wasted motion, and no wasted meat or hide. For themselves and their families, they kept the “skinner’s cuts” – the rumen, the fatty colon (which crisps beautifully when cooked), liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, tongue, and the muscles alongside the windpipe and throat.

Our dinner was a reprise of the delicious wildebeest Stroganoff, with the tenderloins taken from the wildebeest cow that Matheus and I had hunted yesterday morning. We had chocolate cake for dessert, then set the bush TV to Channel 1 and made plans for tomorrow.

The weather has returned to normal – chilly, but not freezing, in the morning, and very pleasant in the afternoon. The sky was clear blue, and we would spend more than two weeks in Namibia before seeing our first cloud!

One of the reasons that I chose Kowas for my safari is that Ansie assured me that my non-hunting wife and friends would have many activities from which to choose. We took advantage of that, asking Matheus to lead the four of us on a morning bush walk, starting from the Kowas lodge and climbing the “mountain” to the summit overlooking the Kudu Waterhole. The windblown Kalahari sand captures animal tracks beautifully. Matheus pointed out the difference between mountain zebra and plains zebra prints. We saw where a mother leopard and her offspring had used the road as a travel route in the night.

Genets, jackals, and snakes all had left their distinctive spoor. There was plenty of wildlife to be viewed, as well: steenbok, duiker, springbok, impala, blue wildebeest, and kudu. Matheus schooled us on the plants, including a tree whose bark the kudu eat to rid themselves of intestinal parasites.

From the top of the mountain, we could see much of the Kowas farm. There was camelthorn savanna where the soils were deep, and a band of short blackhook thornveld where the limestone was close to the surface and the soil shallow.

Looking down at the Kudu Waterhole, we saw a herd of impala, including a ram with a broken horn – perhaps a future non-trophy prospect! A very impressive warthog boar came in for a drink, sporting a long and thick left tusk.

Selma had whipped up a dish of impala lasagne for lunch. Danie generously spent a few hours with us, helping us plan our visit to Etosha, which would follow our stay at Kowas.

Moira, Lucy, and Paul had never been on a big game hunt, so at 1500 we met Matheus and Michael to look for a third non-trophy oryx at the Shoombe farm. The back of the bakkie was packed with people. The little diesel struggled gamely under the load. We picked up a worker at the Shoombe house and began circling the farm on the soft sandy roads, ducking and dodging the low-hanging blackhook and camelthorn branches. Michael did a superb job of maneuvering the bakkie to keep us from losing an eye to a thorn.

Matheus spotted a lone oryx bull (“by the light shining on his horns,” he later told us) bedded down in the long grass at the base of a blackhook acacia. The bull was too close to the road to let everyone join the stalk, so Michael dropped Matheus and me and drove away. We knelt for several minutes to verify that the oryx was focused on the departing bakkie, then moved from bush to bush as long as the oryx’s head was turned. At 95 yards Matheus set up the sticks. The oryx got to his feet to stare at us, but I already had the crosshairs on the point of his right shoulder to make the quartering shot, and was able to shoot quickly before he ran. The shooting lane to the oryx was completely unobstructed by brush – a rarity on this safari. The bullet broke the right shoulder and shredded the vessels at the top of the heart. The oryx stumbled 10 yards, crashed into a camelthorn acacia, and toppled onto his right side.

When Matheus and I reached the oryx the hair was rising on his body, but only on the front third. Matheus pointed out that there was no exit wound, and said that the bullet would be found under skin just at the point where the hair had failed to rise. He touched the point of his knife blade to that spot and the 4-petaled Barnes copper flower popped out into his fingers!

Moira, Lucy, and Paul were impressed by the size and beauty of the oryx, and the respect with which he was treated. I think that most hunters appreciate the seamless connection between the planning, the stalk, the kill, and the meat at the table. But for non-hunters, the idea that dinner was roaming the veld just a few hours before is something of a revelation, and is in stark contrast to the rearing and slaughter of domesticated animals, or the purchase of shrink-wrapped meat at the grocery store.

We watched Matheus, Michael, and Timo skin and butcher the 550-pound oryx with orchestrated precision – never a wasted motion, and no wasted meat or hide. For themselves and their families, they kept the “skinner’s cuts” – the rumen, the fatty colon (which crisps beautifully when cooked), liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, tongue, and the muscles alongside the windpipe and throat.

Our dinner was a reprise of the delicious wildebeest Stroganoff, with the tenderloins taken from the wildebeest cow that Matheus and I had hunted yesterday morning. We had chocolate cake for dessert, then set the bush TV to Channel 1 and made plans for tomorrow.

Last edited by a moderator:

huntermn15

AH fanatic

- Joined

- Sep 28, 2013

- Messages

- 830

- Reaction score

- 544

- Location

- Anchorage, Alaska

- Media

- 8

- Member of

- NRA, SCI, AK SCI

- Hunted

- U.S.A. NJ, TX, AZ, AK. Limpopo and the Kalihari in South Africa. Eastern Cape RSA 2017.

Outstanding report and photos! I look forward to reading more.

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

Outstanding report and photos! I look forward to reading more.

Glad you're enjoying them! I took the leopard photo at Okonjima, between Kowas and Etosha. We saw plenty of leopard tracks at Kowas, but no leopards.

Toby Bradshaw

AH senior member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2013

- Messages

- 50

- Reaction score

- 18

- Website

- home.comcast.net

- Media

- 74

- Hunted

- Namibia, Zimbabwe, Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Texas, Louisiana, Florida

12 July 2014

We spent yesterday on non-hunting activities. In the morning, Danie guided us to a fontein (spring) on the Seifart farm to watch the spectacular morning flight of Burchell’s and Namaqua sandgrouse. They arrived by the hundreds and thousands, lighting for just a moment to drink, then whirling away with their deep, powerful wingbeats. Wave after wave they came, for more than an hour, filling the air with their musical murmuring calls, and then they were gone. Wingshooters, take note! [The photo below is a double-banded sandgrouse, because I didn't get a photo of the Burchell's or Namaqua.]

In the afternoon, Danie led an expedition to look for meerkats, a Kalahari specialty that was on Moira’s wish list. There are only a few meerkats to be found at Kowas, and they don’t like to emerge from the comfort of their burrows when the weather is cold. But Danie came through for us!

Last night’s dinner was especially memorable – Miguel had taken a beautiful bull eland, and there is absolutely nothing better to eat than a well-seasoned medium-rare eland tenderloin steak still sizzling from its brief searing over the glowing camelthorn coals.

But on this morning, Matheus and I wanted to get an early start to search for my lost ammo wallet, a thin brown plastic MTM case that I pocketed to transport my handloads for each day’s hunt. I had reloaded my Sendero from the wallet after shooting the blue wildebeest cow two days ago, but when we returned to the site, the wallet was nowhere to be found. Reluctantly, I wrote off the 5 loaded rounds and one empty brass that were in the wallet. I hated to lose them, but I had plenty of ammo for the remainder of my hunt, having brought 40 rounds altogether.