- Joined

- Aug 21, 2009

- Messages

- 402

- Reaction score

- 162

- Website

- www.africanindaba.co.za

- Media

- 70

- Articles

- 182

- Member of

- CIC, Rowland Ward, B&C, DSC, German Hunting Association, KZN Hunting Association, Wild Sheep Foundation

- Hunted

- Western US, Western Canada, Alaska, Colombia, Tajikistan, Russian Federation, China, Iran, Austria, Germany, Spain, Czech Republic, UK, Indonesia, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Congo, Tanzania, Uganda, Botswana, Namibia

Hunting in Ghana The Royal Antelope

by Steve Kobrine

Editor’s Remarks: The Royal Antelope Neotragus pygmaeus is listed as “Least Concern” in the IUCN Red List 2008 as the total population is estimated at ~62,000 (likely an underestimate), and their secretive nature and ability to utilize secondary vegetation and to persist in small forest fragments should enable it to persist in substantial numbers despite the high-density, increasing human populations over large parts of its range.

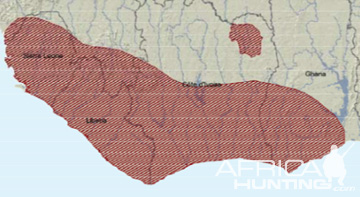

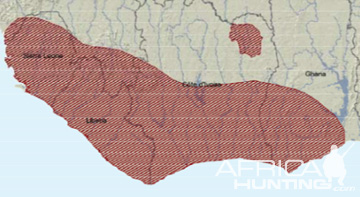

The Royal Antelopes ranges from south-western Guinea (the Kounounkan Massif perhaps representing the westerly known limit), Sierra Leone, Liberia, south-eastern Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, to the Volta R., Ghana (Kingdon and Hoffmann in press). Records from the forests east of the Volta River in north-east Ghana remain questionable (Grubb et al. 1998). Fischer et al. (2002) reported what they considered to be reliable observations of the tracks of Royal Antelopes in Comoé N. P. in north-east Côte d’Ivoire. The world’s smallest antelope species is nocturnal, timid and very secretive. It occupies moist lowland forest and secondary vegetation habitats, forest edges and other areas with dense undergrowth; its range extends into forest- savanna mosaic to the north of the main forest block in West Africa. The Royal Antelope is often encountered more in logged forest with some undergrowth than in primary forest and it is frequently encountered in farm bush (Source IUCN Red List 2008).

Steve Kobrine was instrumental in opening sport hunting opportunities in Ghana. His article gives some impressions about the difficulties of hunting this tiny antelope and we encourage readers to comment on Steve’s proposals.

Steve Kobrine (right) with client and male Royal Antelope hunted in Ghana. Picture by Steve Kobrine Safaris

Distribution Map Royal Antelope

I have been fascinated by the tiny animals of Africa for many years and, over the last three years, have made seven trips to Ghana in pursuit of the most fascinating of them all, namely, royal antelope. During the course of my visits, I met Nana Adu-Nsiah, the executive director of the Wildlife Division of document on Collaborative Resource Management which his department had produced. In the document it is stated that, “People will manage wildlife and other resources when they are provided sufficient incentive to do so. This incentive is primarily an economic incentive and direct financial benefit provides one of the strongest incentives for farmers.”

Given that the trade in bushmeat in Ghana is estimated to be worth between $200 and $300 million dollars per annum and that the Wildlife Division has admitted that the trade in bushmeat is an integral part of the Ghanaian culture which it was not realistic, feasible or desirable to stop, a decision had been taken to try and introduce both trophy hunting and game ranching, on bases similar to that which existed in South Africa, in an attempt to save the remaining game in Ghana from extinction.

During my initial scouting trips, I came to the conclusion that just about the only animals that existed in viable quantities and which might attract dedicated trophy hunters to Ghana, were the royal antelopes, black duikers, Maxwell’s duikers and harnessed bushbucks which existed in the coastal rain forests and thickets bordering the rubber plantations and cassava fields of the locals. Along the coast people can obtain fish as an alternative source of protein and, as such, poaching is not as fierce as in the interior although it often seems in Ghana as if every man owns a Russian made 12 guage shotgun.

In February of this year, Nana Adu-Nsiah personally issued the first hunting licenses to the first to trophy hunters in Ghana in living memory, namely, Katharina Hecker and Peter Flack from South Africa, who were outfitted by my company, Steve Kobrine Safaris, and guided by myself and one of my professional hunters, Ian “Tweek” Roodt. Since then, a further three American trophy hunters have come and gone and another two are due to arrive shortly.

The first hunt was in the nature of an exploratory trip and Katharina and Peter had kindly agreed to act as guinea pigs, both to iron out any initial difficulties and also to help prospect areas for good concentrations of game. Peter is a member of Rowland Ward’s Guild of Field Sportsmen and, as such, had specifically arranged to hunt the strictly nocturnal royal antelopes during the full moon as the rules of the Guild, while allowing hunting with natural light, forbid hunting with artificial light. It is here we struck the first problem. We learnt that a royal antelope can simply not be hunted during moonlight and it is the one time when no one, not even the most ardent poacher, attempts to hunt them.

The three poachers who I have employed to act as game guards under the supervision of the local chief (who is also in my employ), use two cell torches powered by used batteries which throw a dull, yellowy white light for about 20 to 30 paces. The reason is that, if a bright light is shone on a royal antelope, it immediately leaps out of sight. Bearing in mind that these tiny antelope measure approximately 10 to 12 inches at the shoulder and weigh only one and a half to two kilograms, it does not have to leap very far in order to disappear in the thick undergrowth of the rain forests or even the rubber plantations and cassava fields. Having said this, however, these tiny beasts are known to make bounds of up to three metres in length.

The hunter and I follow behind the game guard wearing red cap lamps which only illuminate the ground at your feet and the heels of the man in front. When a royal antelope is spotted, the hunter and I immediately turn off our cap lamps (to avoid back lighting the game guard) and the hunter immediately moves forward and positions his shotgun over the shoulder of the game guard in order to aim down the beam of his torch. This has to be done pretty smartly as, even in the dull beam of the torch, the royal antelope will not stand for more than four to five seconds before scuttling off.

Of the five hunters who have hunted royal antelopes so far, only three have been successful. Katarina shot a female which was facing away with its back to the game guard’s torch as did Tom Hammond and Bruce Keller shot a very good male which may become the new world record in Rowland Ward’s Records of Big Game where, currently, only four animals have been recorded as meeting the minimum entry level of one inch in the 117 year history of the book. Of the remaining two hunters, Peter did not want to shoot one as it would contravene the Code of Conduct of Rowland Ward’s Guild of Field Sportsmen and the remaining hunter, unfortunately, wounded two animals for which he paid in full.

And this brings me to the crux of this brief article. All five trophy hunters, Peter included, agreed without reservation that these arduous, walk and stalk hunts, at night, in the heat and high humidity of Ghana’s dense coastal rain forests, were fair chase in every respect.

Now I am a great fan of Rowland Ward and its record book, which not only serves as a good reference source for hunters but, by setting high minimum entry levels, encourages hunters, for the most part, to shoot only the older animals. In addition, the modern fad of awards for shooting animals is not part of this traditional record book and the animal certainly receives as much recognition as the hunter himself. In fact, I have been considering becoming a member of the Guild but now I find I can’t. My question, therefore, to African Indaba readers, in general, and Rowland Ward’s Guild members, in particular, is, do you not think that an exception should be made to the natural light rule set out in the Guild’s Code of Conduct insofar as royal antelope are concerned?

My request is based on three fundamental reasons, firstly, the hunt is fair chase and, as the animal is strictly nocturnal, there is no other way of hunting it. Secondly, we know that hunting an animal in Africa is the surest way of conserving it – South Africa has conclusively proved this with the Cape mountain zebra, the bontebok, the white rhino and the black wildebeest.

Finally, I can think of no other way to stop this beautiful tiny antelope becoming extinct in a country where commercial bushmeat poaching is a way of life.

For more information on hunting the Royal Antelope, contact Steve Kobrine Safaris.

by Steve Kobrine

Editor’s Remarks: The Royal Antelope Neotragus pygmaeus is listed as “Least Concern” in the IUCN Red List 2008 as the total population is estimated at ~62,000 (likely an underestimate), and their secretive nature and ability to utilize secondary vegetation and to persist in small forest fragments should enable it to persist in substantial numbers despite the high-density, increasing human populations over large parts of its range.

The Royal Antelopes ranges from south-western Guinea (the Kounounkan Massif perhaps representing the westerly known limit), Sierra Leone, Liberia, south-eastern Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, to the Volta R., Ghana (Kingdon and Hoffmann in press). Records from the forests east of the Volta River in north-east Ghana remain questionable (Grubb et al. 1998). Fischer et al. (2002) reported what they considered to be reliable observations of the tracks of Royal Antelopes in Comoé N. P. in north-east Côte d’Ivoire. The world’s smallest antelope species is nocturnal, timid and very secretive. It occupies moist lowland forest and secondary vegetation habitats, forest edges and other areas with dense undergrowth; its range extends into forest- savanna mosaic to the north of the main forest block in West Africa. The Royal Antelope is often encountered more in logged forest with some undergrowth than in primary forest and it is frequently encountered in farm bush (Source IUCN Red List 2008).

Steve Kobrine was instrumental in opening sport hunting opportunities in Ghana. His article gives some impressions about the difficulties of hunting this tiny antelope and we encourage readers to comment on Steve’s proposals.

Steve Kobrine (right) with client and male Royal Antelope hunted in Ghana. Picture by Steve Kobrine Safaris

Distribution Map Royal Antelope

I have been fascinated by the tiny animals of Africa for many years and, over the last three years, have made seven trips to Ghana in pursuit of the most fascinating of them all, namely, royal antelope. During the course of my visits, I met Nana Adu-Nsiah, the executive director of the Wildlife Division of document on Collaborative Resource Management which his department had produced. In the document it is stated that, “People will manage wildlife and other resources when they are provided sufficient incentive to do so. This incentive is primarily an economic incentive and direct financial benefit provides one of the strongest incentives for farmers.”

Given that the trade in bushmeat in Ghana is estimated to be worth between $200 and $300 million dollars per annum and that the Wildlife Division has admitted that the trade in bushmeat is an integral part of the Ghanaian culture which it was not realistic, feasible or desirable to stop, a decision had been taken to try and introduce both trophy hunting and game ranching, on bases similar to that which existed in South Africa, in an attempt to save the remaining game in Ghana from extinction.

During my initial scouting trips, I came to the conclusion that just about the only animals that existed in viable quantities and which might attract dedicated trophy hunters to Ghana, were the royal antelopes, black duikers, Maxwell’s duikers and harnessed bushbucks which existed in the coastal rain forests and thickets bordering the rubber plantations and cassava fields of the locals. Along the coast people can obtain fish as an alternative source of protein and, as such, poaching is not as fierce as in the interior although it often seems in Ghana as if every man owns a Russian made 12 guage shotgun.

In February of this year, Nana Adu-Nsiah personally issued the first hunting licenses to the first to trophy hunters in Ghana in living memory, namely, Katharina Hecker and Peter Flack from South Africa, who were outfitted by my company, Steve Kobrine Safaris, and guided by myself and one of my professional hunters, Ian “Tweek” Roodt. Since then, a further three American trophy hunters have come and gone and another two are due to arrive shortly.

The first hunt was in the nature of an exploratory trip and Katharina and Peter had kindly agreed to act as guinea pigs, both to iron out any initial difficulties and also to help prospect areas for good concentrations of game. Peter is a member of Rowland Ward’s Guild of Field Sportsmen and, as such, had specifically arranged to hunt the strictly nocturnal royal antelopes during the full moon as the rules of the Guild, while allowing hunting with natural light, forbid hunting with artificial light. It is here we struck the first problem. We learnt that a royal antelope can simply not be hunted during moonlight and it is the one time when no one, not even the most ardent poacher, attempts to hunt them.

The three poachers who I have employed to act as game guards under the supervision of the local chief (who is also in my employ), use two cell torches powered by used batteries which throw a dull, yellowy white light for about 20 to 30 paces. The reason is that, if a bright light is shone on a royal antelope, it immediately leaps out of sight. Bearing in mind that these tiny antelope measure approximately 10 to 12 inches at the shoulder and weigh only one and a half to two kilograms, it does not have to leap very far in order to disappear in the thick undergrowth of the rain forests or even the rubber plantations and cassava fields. Having said this, however, these tiny beasts are known to make bounds of up to three metres in length.

The hunter and I follow behind the game guard wearing red cap lamps which only illuminate the ground at your feet and the heels of the man in front. When a royal antelope is spotted, the hunter and I immediately turn off our cap lamps (to avoid back lighting the game guard) and the hunter immediately moves forward and positions his shotgun over the shoulder of the game guard in order to aim down the beam of his torch. This has to be done pretty smartly as, even in the dull beam of the torch, the royal antelope will not stand for more than four to five seconds before scuttling off.

Of the five hunters who have hunted royal antelopes so far, only three have been successful. Katarina shot a female which was facing away with its back to the game guard’s torch as did Tom Hammond and Bruce Keller shot a very good male which may become the new world record in Rowland Ward’s Records of Big Game where, currently, only four animals have been recorded as meeting the minimum entry level of one inch in the 117 year history of the book. Of the remaining two hunters, Peter did not want to shoot one as it would contravene the Code of Conduct of Rowland Ward’s Guild of Field Sportsmen and the remaining hunter, unfortunately, wounded two animals for which he paid in full.

And this brings me to the crux of this brief article. All five trophy hunters, Peter included, agreed without reservation that these arduous, walk and stalk hunts, at night, in the heat and high humidity of Ghana’s dense coastal rain forests, were fair chase in every respect.

Now I am a great fan of Rowland Ward and its record book, which not only serves as a good reference source for hunters but, by setting high minimum entry levels, encourages hunters, for the most part, to shoot only the older animals. In addition, the modern fad of awards for shooting animals is not part of this traditional record book and the animal certainly receives as much recognition as the hunter himself. In fact, I have been considering becoming a member of the Guild but now I find I can’t. My question, therefore, to African Indaba readers, in general, and Rowland Ward’s Guild members, in particular, is, do you not think that an exception should be made to the natural light rule set out in the Guild’s Code of Conduct insofar as royal antelope are concerned?

My request is based on three fundamental reasons, firstly, the hunt is fair chase and, as the animal is strictly nocturnal, there is no other way of hunting it. Secondly, we know that hunting an animal in Africa is the surest way of conserving it – South Africa has conclusively proved this with the Cape mountain zebra, the bontebok, the white rhino and the black wildebeest.

Finally, I can think of no other way to stop this beautiful tiny antelope becoming extinct in a country where commercial bushmeat poaching is a way of life.

For more information on hunting the Royal Antelope, contact Steve Kobrine Safaris.

Last edited by a moderator: